Inside the Jewel Vault with Dr Sandra Hindman

Listen Now

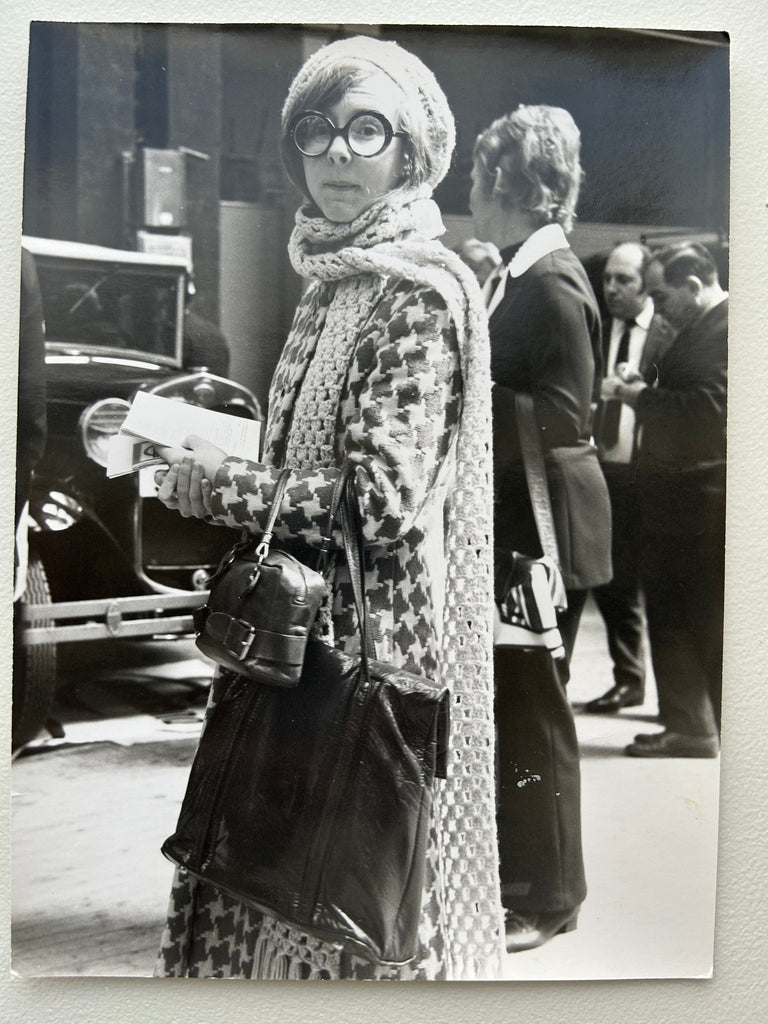

Sandra at TEFAF Maastricht |

|

|

|

|

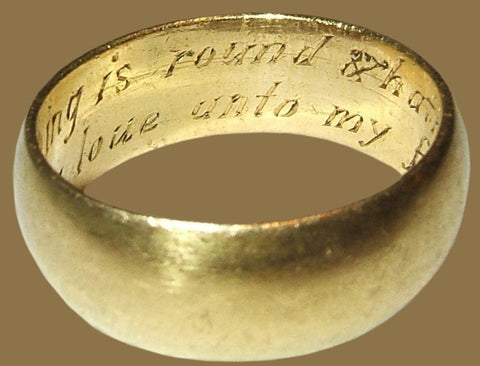

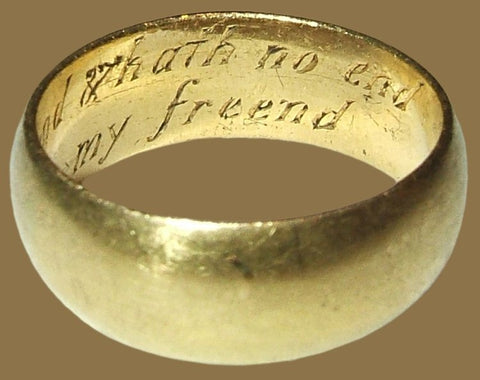

![Posy Ring "[...] So is my loue unto my freend" England, c. 1590-1600 - Juraster](https://cdn.shopify.com/s/files/1/0648/5091/9652/files/W_366c_514a0e02-2c5e-4ea8-a602-c1f3d28a1948_480x480.jpg?v=1690445449) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

JCC: Sandra Hindman is the founder of leading antique dealer Les Enluminures, which she started over 30 years ago in 1991, and now has three galleries in Paris, Chicago, and New York. She's a specialist in rare, illuminated manuscripts and books, and her expertise also covers precious works of art in gold and gems, posy rings, antique jewels, and archaeological treasures. In addition to overseeing the activities of her three busy galleries, Sandra travels to many international art fairs and book fairs. And she's a certified GIA alumnus, a professor Emirata of Art History at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, and has written 18 books, 35 reviews, over 60 catalogues, and she speaks three languages and reads six. Welcome, Sandra. I can't wait to see what you have for us Inside the Jewel Vault.

SH: What fun it is to be here, Jessica, I'm a fan of your podcast, and I'm just delighted to now participate in one, although I have to say it was very difficult to prepare to pick only six things.

JCC: You had hundreds of pieces that I'm sure you wanted to put in.

SH: Right!

JCC: It is very strict, isn't it? Only six pieces from such a long career. But tell us where it all started, because you're from Chicago, is that right?

SH: Originally. Yeah, I am from Chicago. My parents are both Californians, and they grew up and went to school and university in California. But my dad was asked to come to Chicago to be on the Manhattan Project. The Manhattan Project was the project that created the atomic bomb in World War II. So, I grew up, sort of in the back steps of the University of Chicago in Hyde Park, where he worked and where that scientific project was based. So, you know, I grew up as a child of an academic, too, because that was my father's job, although a scientist, not an art historian.

JCC: But where did you get your love of art and history and these beautiful shiny objects that you've put into your Vault for us?

SH: Right. Well, I think it really comes from my mother. My mother took me even when we moved to the suburbs, my mother took me to the Art Institute of Chicago, which is a fantastic museum. On weekends, I remember going there. I still even remember which paintings were at the top of the stairs. And, from a middle-class family, they weren't art collectors, but my mother loved art, and she bought all these, like, reproductions of paintings. I mean, my room as a child had, again, a reproduction, but a Degas, a Renoir and a Modigliani that I looked at all the time. So, I think my interest in art came from her and also, not when I was a child, but later, she collected rings. She collected Victorian rings and sort of not like, an obsessive collector, more as a shopper. She liked them and wore them and wore all of them. And, I have some of hers now too. So I guess the rings come from that also and from just my general interest in the Middle Ages.

|

Sandra as a grad. school student |

JCC: So, tell us what happened at school then. Were you allowed to pursue your interest in Art and Art History? Were you creative at school or well, in your intro, we can see clearly how academic you are.

SH: Yeah, I mean, school like probably most people of my generation, I wanted to be many different things in high school. It's like I explored a million different things, but I wanted to be like my father. So, I went to, college to be a scientist. And I had done this advanced science project in high school, although I had done you couldn't do Art History in my high school, but I had done French and literature. Anyway, I went to the University of Chicago to become a scientist and I got a D in Freshman math. So it was like, well, I guess I need to change. And this is like the very first semester. I even made my brother hide my report card. I was so embarrassed. And I was always interested in French and I was taking French then too, and sort of debated majoring in French. But Art History at University of Chicago was awesome. I mean, some of the greatest Art Historians of that generation taught there. It was really a good program. And, I was already taking Art History by sophomore year and my junior and senior year I was taking mostly Medieval and Northern Renaissance. So really who I am academically already started at University. |

JCC: I can see then. So, this is why you were surrounded by this early love and now you were able to put it into your academic blossoming. So, tell us about the jewellery side of things. I mean, you explained your mother loved rings and you had a fascination for it. Is there anything you've put into your Jewel Vault that you can trace to your mother or her love of rings?

|

Iconographic ring, 15th century. |

St Anne teaching The Virgin to read. |

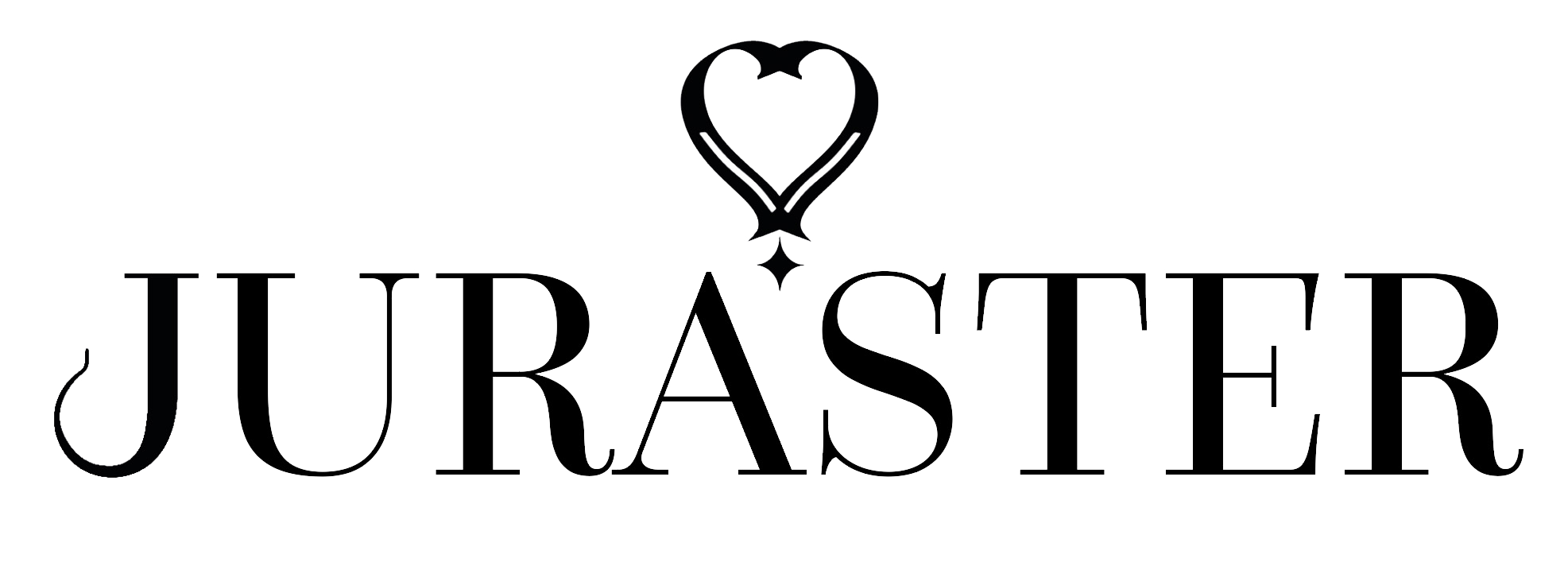

SH: Well, I think the very first thing that I want to put in my jewel box is directly related to the beginning of my interest in rings and at the same time related to my mother, and related to my later career as an art dealer. So, it sort of summarises a lot of different aspects of my life. The very first art fair I did, where I made no money, basically, because that's what happens when you start something, at the end, maybe we sold some little thing. I rushed to another, jewellery booth, and I bought an iconograph. We're talking 30 years ago, and I bought an iconographic Medieval ring.

So iconographic rings. It's a dumb name, sort of, that Victorians have given to a type of medieval ring. And it basically just means a ring with a picture on it. And these rings with pictures on them have pictures mostly of saints, a little icon of a saint, as it were. And they're almost all English, 15th century. And some of them are inscribed, too. So my iconographic ring has a picture of the Virgin Mary, with St. Anne, who was her mother. And they are holding a book because the story is that St. Anne taught the Virgin Mary to read. So, I always say this is the perfect ring for me. It's like a mother and a daughter and a book. It is a medieval manuscript because they wouldn't have had another book in the 15th century. Like I said, mother and daughter and a book. I sometimes say, this is my marriage ring, my wedding ring, because I'm married to manuscripts. But also some of these rings are inscribed, and in England, at a certain class in the 15th century, spoke French, not English. And my ring says, ‘Null si bien’. Or no one's better than you, or you're the best. So, my fantasy is that this ring was given by a mother to her daughter in the 15th century. And it kind of commemorates my relationship with my mother and my interest in rings. And I actually wear it every day. In fact, I even swim with this ring, although I tell clients, you're not supposed to swim with your rings, but, I swim with mine!

JCC: I think that's very special and very moving, actually, because there it is, this direct link to your mother and jewellery. It's just beautiful. And you've sent a picture of it so I can have a look. And, it's very finely detailed. It can't be a very big ring?

|

SH: No, it's tiny. Yeah, it's tiny. JCC: How many hundreds of years old did you say it's? SH: So it's about 1450. So that makes it almost 600 years old. JCC: Amazing. SH: But I sort of think that, I feel like jewellery. It's so exceptional from the Middle Ages because it is wearable art. I mean, it's incredible. And my little ring, I mean, unless you know what you're looking at, nobody has any idea what I'm wearing. It's not bling. It's something like you wear a medieval jewellery for yourself, not for others. You wear it - a medieval iconographic ring. You touch it like you would maybe touch the saints in your little Book of Hours. JCC: So that you're feeling - with your fingertips, you can almost touch them. SH: That's right. That's right. JCC: Well, that's magical. Thank you. JCC: So, we got to your studies - what happened next? SH: Well, I did go on for both a masters and a doctoral degree and three years in London and two, writing my dissertation. So I did a lot of years of study. I was at Berkeley for two years. I was in Ithaca, New York, for two years, and I was in London at the Warburg Institute for three years. So that's kind of a lot of living different places and traveling different places. JCC: It certainly is. And what did you do your doctorate in? SH: So always Art History and always Medieval. But at Berkeley I met someone who, his name is L.M.J. Delaisse and he was this amazing man. He had been in the Resistance, he’s Belgian, and he had been in the Resistance in World War II. He had lost a leg, and he had very difficult movement with his other leg, but he had this human approach to Art History. Everything had to be about the people and the makers and the users. I worked on a series of Dutch illuminated bibles but made them seem really personal. So that was my dissertation, and then it was also my first book. There were no jewellery - you never, ever studied jewellery or rings in Medieval Art History. Now you probably do, but the decorative arts, quote unquote, were just not there. |

Sandra as a grad. student in London |

JCC: Right. How interesting. So do you feel that, this was something that you have brought into, you've developed this area of the specialty yourself?

SH: Is it something that I do feel that when I started to buy and handle jewellery as part of my business, the very first book I wrote, on jewellery was called “Toward an Art History of Medieval Rings”. And in that book, I explain that there was no study like this, that rings were approached in the relationship maybe to literature a little, or social context, but there was absolutely nothing on how they fit in different architectural movements. I mean, nothing. So, I really consider that book a kind of major monument in the study of rings and jewellery as part of the larger field of Art History. I already talked about the iconographic ring and Books of Hours. So in relating iconographic rings to miniatures, pictures, in 15th century English illuminated Books of Hours, I was situating iconographic rings within a larger picture, a larger history of art.

JCC: How interesting. So really, do you feel that that's one of your great legacies? Other than the fact you're a pioneering woman running an international art and jewellery dealership, you've also led to this new paradigm - way of looking at - interpreting jewellery?

SH: Yeah, I think so. I'm not too into legacy ideas, but yeah, I guess, I mean, you know, I had fun doing it. It's interesting to see it taken up in the literature or other things like the medieval rings that are called stirrup rings. And it's also a term invented in the 19th century when they first started to think about and study rings. And it's because they look like a horse's stirrup. But, in fact, in working on studying the origin of stirrup rings, it coexists with the origins of the Gothic cathedral. So, a stirrup ring is actually a Gothic arch. It's not a horse's stirrup, of course. So the origins of Gothic architecture are tied up with stirrup rings, which were given mostly to bishops.

JCC: Yes. So, I can understand because I've always struggled with the name stirrup ring. How on earth is this supposed to be related to anything equestrian? You clarified it for me, so thank you. I know we've sort of veered away a little bit from your Vault. So have you got a second item in here?

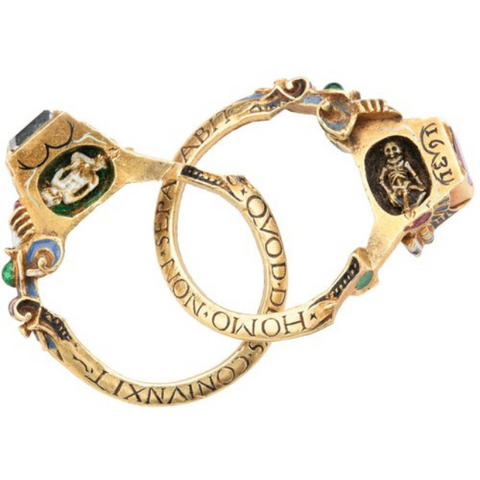

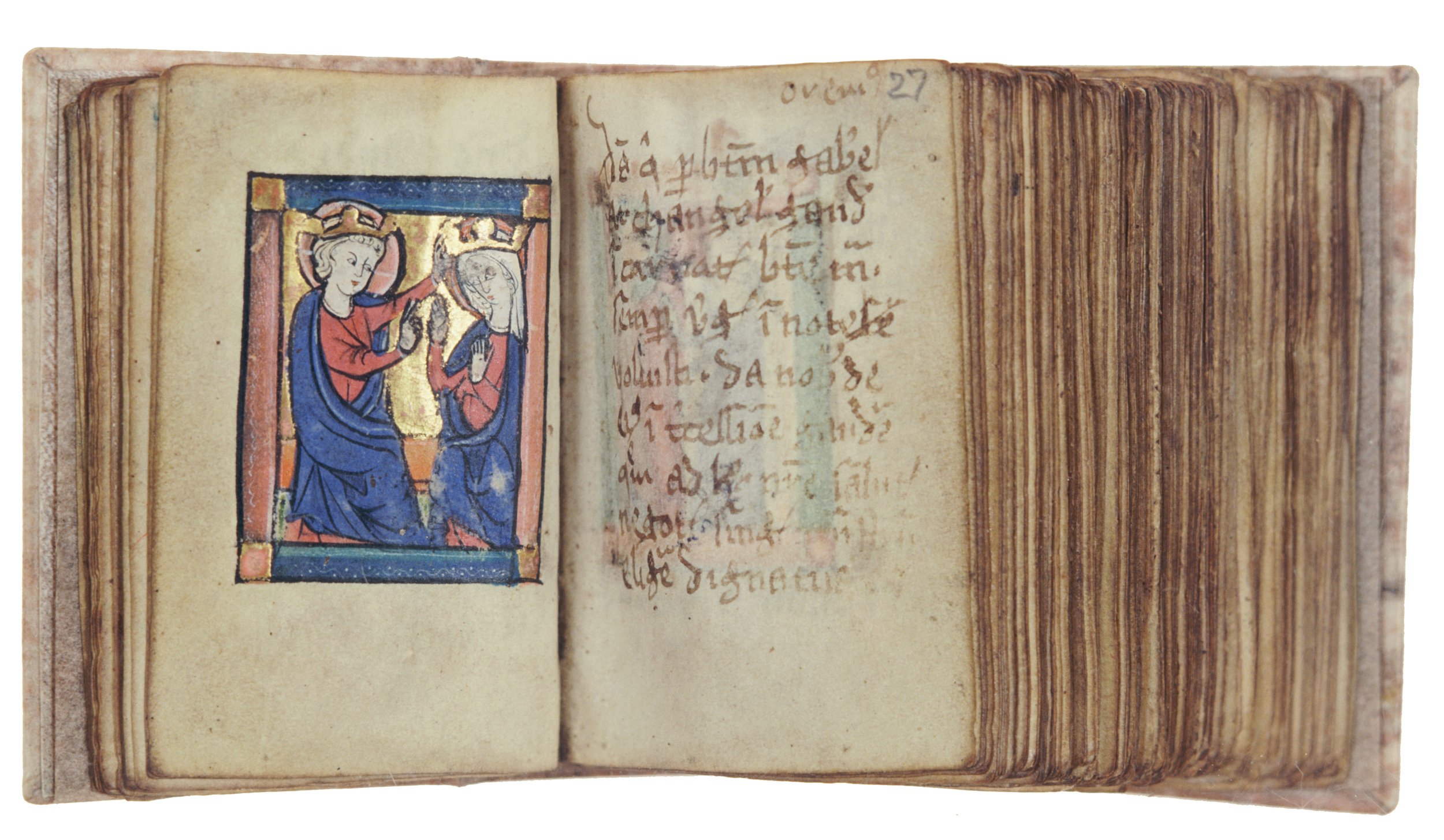

Miniature Medieval psalter, 13th Century

SH: I do have a second item, and it might surprise your listeners because, it is a book. Yes, but it is a miniature psalter, but it's tiny. It is an inch and a half by two inches in size. So it's the smallest 13th century manuscript known, but it has eight pictures in it, and text, but really big text, because obviously it's so small, you need to read it. But the thing is, it must have been worn. And it would have been worn in a little pouch around the neck. And then you could pull it out of the pouch and open it and read your psalms and look at the pictures. So, I've put it in my Vault because there's a new term that's used, in fact, I wrote a blog on it, bibliomorphy. So, it's books that morph into something else. So, it's a kind of book-jewel. It's as much a jewel as it is a book. And people often say to me, you're a medieval manuscript dealer, scholar. What does jewellery have to do with it? But, I put this in my Vault because it really explains to me the relationship between jewels and books. They're small objects. They're intimate objects. This is a book that can be worn, like a jewel can be worn. They're made of similar materials. I mean, gold and lapis lazuli and precious stones. The blue in medieval manuscripts is lapis lazuli. So, it's a precious gemstone. So, I love this manuscript. I mean, I handled this. This was in my second catalogue nearly 30 years ago and it's had two different owners since. But now it's in a museum. So, regrettably, it's in their Vault. I'm like kind of metaphorically putting it in my vault, but I probably can't get it back.

JCC: So, in your fantasy and for this moment, it is in your vault.

SH: And then I've described it and it's probably from Lorraine, which was very important. Certainly, it was for someone very highly placed. Medieval manuscripts were expensive then, as they are now. And a psalter is, of course, part of the Bible. And this is actually in the Bible Museum.

JCC: Is it really? So where is the Bible Museum?

SH: It's a museum that's in Washington DC.

JCC: So we'll have to travel there when we go to the Smithsonian?

SH: That's right.

JCC: Exactly. What a wonderful piece. Thank you so much. So, the third item in here, tell us about this, because this is now - it looks like a ring. So, tell us about this.

|

|

|

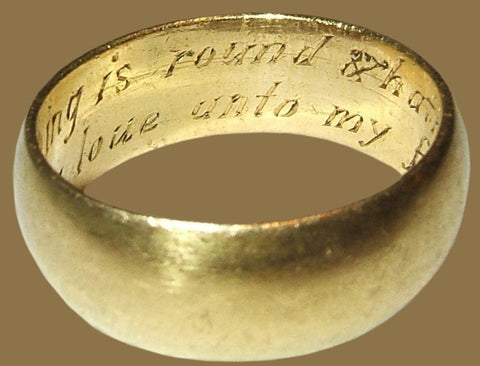

SH: It's a posy ring. So posy comes from poésie or poetry. And there are a lot of posy rings, and we handle a lot of them. And I've written on them. So, they originate in 16th century England and they go through the 18th century. Most of them are English and most of them have English inscriptions. In fact, Shakespeare writes about posy rings in Hamlet. Someone says, “Is this a prologue? Is this a prologue or the posy of a ring? And I think it's Ophelia who answers, “Tis brief, my lord, like woman's love”. But my favourite posy ring, rhymes, because posies are meant to rhyme and it's quite long. It says, “This ring is round and hath no end. So is my love unto you, my friend” and, it's inside because the idea is only you and the person who gave it to you know what it says. So, it's kind of this secret message. and because it’s so long, it's on like two, it's a thick band, and a big ring because it has to be on two lines, one above each other. But I love how rings - posy rings - refer to the ring and the wearer. It's like speaking jewellery, and worn on the body with the language toward the finger. They're like speaking to the person, quite literally. I don't know. There are lots of posies. They're not only love rings or marriage rings. There are a lot of posies that say “A friend's gift”, for example. Or, I think this posy is apocryphal, but I have an important collector of posy rings who has said to me, if you ever get this posy, this is the posy I want. And purportedly it says, “Meet me at the garden gate at midnight”

JCC: I have to say, Sandra, I think the first time I came across your pieces, your business, was at Masterpiece in London years ago, and you had this fantastic array of glittering books. But in front of that was this amazing array of posy rings. And I've always found posy rings just so lovely, romantic and delightful. So, as you say, they are speaking jewellery. It's such a nice way to put it. You wrote a book, didn't you, on posies?

SH: You know, I'm not the one who wrote the book, but I formed a collection, an important collection of 130 and 140 posy rings for a private collector called the Griffin Collection. And my good friend, and we'll get to her, Diana Scarisbrick, wrote the book then, on this collection, and we helped her publish it and, get the pictures and sort of were the intermediary between the collector and Diana, and that book that she wrote, which just came out, like, last year, Paul Holberton, in London. That's a kind of redoing of Joan Evans book on posy rings from 1931. So, it's I mean, Diana's a wonderful person, a great scholar on this new book, which actually she titled “I Like My Choice”.

JCC: Well, yes, it's wonderful that you've had the opportunity to redo a book by Joan Evans, who is such, pioneering - amazing.

Wonderful, thank you. So we've got three lovely pieces. Now we've got your your iconographic ring. And you've got this wearable book, the miniature psalter and the posy ring. So what is item four? What does it tell us about you and your journey?

Amuletic ring of a cat & her kittens,

Egyptian 18th Dynasty, faience.

SH: Well, item four, I've talked about becoming a dealer and dealing also in jewellery. You mentioned my founding my gallery in ‘91. But, as a result of this book, the “Towards an Art History of Medieval Rings”, I met someone who's been very important in my life and has become a friend. And his name is Benjamin Zucker. And I acquired Benjamin Zucker's ring collection. He's a diamond dealer. Third, fourth generation diamond dealer. And he'd always collected rings, diamonds too, but that's another story. And as one of, his, favourite rings, which he tells me he kept, like as a treasure in a box wrapped up in tissue, he never took it out of the box. I bought this Egyptian ring made out of pottery – faience - of a cat in her kittens. The cat standing up and all her little kittens are in front of her. And this would have been amuletic. if you've wanted children, you have this cat and kittens ring. The Egyptians were very devoted to cats I mean, they had cat mummies that they put in sarcophagi with the owners of them. But this cat and kittens ring is extremely rare, very fragile. That's why Benjamin never took it out of this box. He said he was so terrified of like, dropping it. And so I put it in a book that I called “Cycles of Life”. And of course, I put it in the first, cycle, which is birth, because it's amuletic and focuses on the birth that this cat had and that this owner is then going to have. And so, it's related both to my long-term relationship with Benjamin. I've sold different parts of this collection over different years and also we sold it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. So, it can't be in my Vault anymore, but it's in their vault. And it's definitely one of the things I would put in my Vault, yes.

JCC: And it's faience, which is a form of glazed, silica-based paste, isn't it?

SH: Right. Very fragile, very lightweight. I mean, this ring, which, you know, to put a cat and or kittens, you know, and surrounding it with, foliage, I mean, it's only 3 grams and very light weight. You can imagine. Like this was Benjamin's fear. He'd take it out of the box and unroll the tissue paper and fall on the floor and be in a million pieces. And in fact, in fact, there is a tiny break in it. And there were originally eight kittens, but now there are only seven. So, it did break at some point.

JCC: Just a tiny bit, yeah. Well, it's hardly surprising because you've dated it to, what - 1200-1300 BC?

SH: Yeah. But around 1300-1500 BC, the 18th Dynasty.

SH: But that is one of the incredible things about historic jewellery, is their survival. The fact that they've survived so long is astonishing.

JCC: Yeah, well, it's magical. So thank you very much for putting that in here. That's a delight. I've never seen anything quite like it. So, tell us about item five, because that resembles a cat as well.

SH: Yes, from a domestic, little cat to a big cat. So, this is a big cat. It's actually called the Althorp Leopard, and it's a crouching leopard made out of moss agate, which is a quite rare type of agate. It's got little green flecks in it. And so, the type of stone must have been very consciously chosen to be able to bring out those flecks in the fur of the leopard.

It's in my vault, not only because it's such an extraordinary object, but this, too, has a relationship to an important person for me, which is Diana Scarisbrick, because this was a ring that was in Diana's collection. She owned it for decades and decades. And, before I did a little book on it, she published on this ring at least five different times. And I was able to acquire it. And then it's gone into, the same private collection that we talked about for the posy ring collection. But it's an extraordinary object. This is, almost lying down, ready to pounce, ready to get up and pounce. And it was made in Milan, in the 16th century, you know, by an important team of cameo carvers. And it's got such an incredible provenance. I mean, it ends with Diana and then with the Griffin collection with me as the intermediary. But it belonged to Pope Clement V. It was a papal gift from Pope Clement to the Emperor Eugene of Savoy. And Eugene of Savoy, in Austria, wore it on his deathbed it was so important to him. And it went through I mean, to know this much we've talked about how rare they are in their survival. But to know this much about the provenance of something is extraordinary. And to have so many famous people, because from Eugene of Savoy, it went to this really, really important Venetian gem collector, Zanetti. And from him, it went to the Spencer collection, in Britain. And in fact, it was only sold from the Spencer collection when Diana, Princess Di was 17 years old. So, she grew up in the house where this ring was. And then it went to Diana Scarisbrick.

JCC: It's had quite a regal and papal ownership it's not just any leopard, then.

SH: No, at all. No, it's not at all any leopard. And probably the Spencers remounted it. We know it was a ring originally because it was worn on Eugene, of Savoy's finger. But it is now in an 18th century very pretty diamond setting that speaks to the era of the Spencers. And as I said, at the height of sort of Milanese lapidary art. In fact, Diana has just, written a book called “The Art of the Ring” on this same private collection. And it's one of the two, kind of highlights, in that book. And I just edited a book with two co-editors, on Diana's life and with 20 different articles dedicated to Diana. And this is one of the two rings that we put in that book to sort of signal something that she's not really known for, which is her life as a collector, as well as one of the world's leading jewellery, historians.

JCC: Wonderful. Thank you. Gosh, there's so many stories to tell about your pieces, but this is really amazing, isn't it, the lives and the situations and the palaces and the travels that this ring must have enjoyed. It's amazing. And the leopard, of course, means, is the animal chosen by the Goldsmith Company here in London to represent them.

SH: I've forgotten that. That's right. That's great.

JCC: Yes. So it's a very special beast, thank you so much. So where are we now? We've got five pieces in here that represent your early beginnings in, your interest in jewellery: the iconographic ring that reminds you of your mother and her love of art and is such an integral piece of your everyday jewellery, you wear it every day. Then we've got this beautiful psalter, the miniature psalter, no bigger than a postage stamp with these delightfully intricate and jewel like illustrations in them. Then we've got the posy ring with this beautiful rhyme. “This ring is round and hath no end. So is my love unto my friend”, this lovely ring. And then we've got the cat and her kittens all the way from the 18th Dynasty in Egypt. And the leopard crouching and ready to spring into its papal or regal intrigue. What is item six?

|

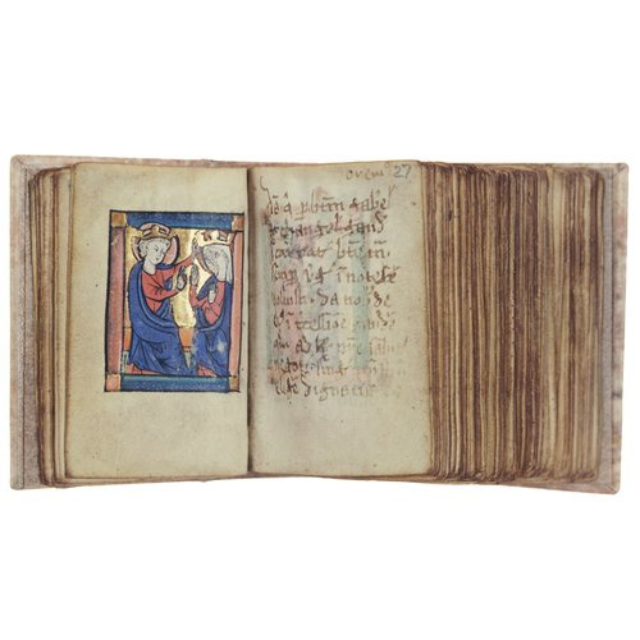

Ruby and diamond gimmel ring, 1630 German |

The gimmel ring open to show memento mori |

SH: Item six. Well, this is also a ring whose journey is incredible. And I picked it – you know, as I've already said, I like doing the research on these. I mean, I'm an academic as well as a collector and a dealer, and I've talked about some of the people. And this is a ring that also came to me via Benjamin Zucker and his collection. But this is a gimmel ring. And gimmel means twin, in Latin gemellus. And it's an inscribed gimmel ring. So twin rings are rings that go together and come apart, not completely apart. They were often used as tokens of marriage. Like, Martin Luther had a gimmel ring when he married. So, this gimmel ring, had an inscription on it and a date. But nobody knew exactly who these people were. So, I found these people, because their names were on it. And it was given on the date of their marriage. A German couple. Martha Wurman and Jacob Sigmund in Hamburg. He was a city official. And, it must have been a wedding ring. That's the date of their marriage. And it says, “Man must not divide those whom God has joined together”. And then inside it has a baby in a little cavity on one side and a skeleton on the other side. So, it's like a memento mori. Like, think about your life. Do good things in your life. And it has, the two most important love jewels. A diamond, a beautiful diamond and a ruby, when it comes together. And then gorgeous enamel along the side.

JCC: It’s very colourful. I've never seen anything quite so... It's in immaculate condition.

SH: It's in amazing condition. The enamel, often the enamel is scraped, rubbed, or gone and the enamel is nearly perfect. So, talking about journeys, so not only did I find where this ring was in 1631, but I found where this ring - I knew where this ring was when I got it, with Benjamin Zucker. But I found that this was a Rothschild ring that had been taken from him by the Nazis. And this ring went to the salt mines, and it was in the same salt mine where the Ghent altar piece was in Austria. And I had this, like, vision, this tiny little ring, like, sitting on the panels of Ghent altar piece. Like, why didn't it get lost? It's extraordinary that it survived. And the reason why I know it was there is I got the record, you know, the Monuments Men who rescued - the so called Monuments Men after the movie - rescued this art, and it all went to Munich and a clearing house, and they recorded each item, and then they gave it back to the owners. So it was given, it was restituted after the war, after being recorded in Germany. And then the Rothschilds sold it. And in an important, a really important kind of Wunderkammer exhibition in London. Benjamin and then I got it, and then I catalogued it and learned all this about it. So it's just, I mean, the combination of how beautiful the ring is, how we are able to know where it was made and for whom and how romantic that was. And their marriage only lasted three years. She died. So, it makes it even more, like, tragic and moving. And then that it went to the salt mine and survived all that. And here it is.

JCC: Incredible. What a story. So I can see why this is the sixth item, because up until this point, you've been wowing us with your choices, but this is really - it deserves its own movie!

SH: Right. If they'd known about it, it should have been in the Monuments Man. Matt Damon could have held it in his hands and said, “Look what I found”!

JCC: So I love the fact - we've got two images here of the inside of the gimmel ring, which has got the little tiny skeleton - that: don't forget death and also that life follows death. It's like an eternal cycle. Part of the ring, metaphor. And then you've got the two different gems sitting on the top. So it's the male and the female and the diamond and the ruby. So, the diamond symbolises what, what did the diamond symbolise to someone in 1631?

SH: I mean, love, the diamond, you know, it's the hardest stone. It was used as a marriage symbol then too. I mean it symbolizes love. And this is a very, very - this is a table cut diamond at an early moment. And then the ruby is also, I mean, red like the heart. The ruby is the second most important, I would say stone, symbolic of love.

JCC: And is that more about passionate, earthly love, whereas the diamond is more about the purity of everlasting true love.

SH: Yeah. Yes, exactly. Indestructible diamond and the warm heart. So, combining these two things and the sort of visual symbolism of the stones, themselves.

JCC: It's a life in a ring, really, isn't it? It's wonderful.

SH: Yeah. Rings have a life, as do manuscripts. That is a good way of putting it.

JCC: I love it. So what's in the future, what's next, do you think? It must have been difficult during the COVID years not to travel, not to see people, not to be active.

SH: Yeah, I travelled a lot. I mean, I travelled the same as I always travelled, which is astonishing. I would be, like, the only person in my cabin on an airplane. I did travel. We did a lot of online, events. But next in rings, I've been buying for a very long time books that have to do with jewellery. Either they're designed they go from the 16th and 17th century, the statutes of the Goldsmith Guild in Bruges, where it was a very important guild. That's one of my manuscripts that has to do with jewellery up to lists of diamond prices, and descriptions of them in the 18th century, and then up to the 19th and 20th century, I've been buying albums of designs for jewellery. And so I guess next is with a colleague of mine, who I know has done a Vault into the Vault thing with you, Beatrice Chadour Sampson. We're going to do a book on these jewellery books.

JCC: Wow. So a book of books? Not just any books.

SH: A book of books on jewellery. They are combining everything

JCC: Wonderful. Well, it sounds like the culmination of your long career. What a wonderful Vault. It really is. And I'm going to ask you the question you've probably been dreading me asking. Quite apart from the very difficult task of choosing just six items, of the thousands of pieces you must have seen and handled, what one piece would you save forever and keep safe in your Vault?

SH: Well, it's not the most invaluable piece, let's put it that way, of these, but you probably can guess. I bet if I pause for a minute and all of your listeners can like guess, they might be right. And it would be the iconographic ring, simply because it's so important for who I am and where I come from. And I've even written a very important article now, if I can say so myself, on iconographic rings and we have a database that we're tracing all the iconographic rings. But for me it's just so meaningful and I, don't know, so, I - meaningful, I mean, 30 years I've worn it on my finger!

JCC: Yeah. So it’s part of you?

SH: Yes, it is part of me. So it can't come out of the Vault? I mean, the Vault being my finger.

JCC: Part of your life forever. Okay. I love that, Sandra. It's wonderful. Wow. Thank you so much, Sandra. It has just been such a joy.

SH: Jessica, it's been really a pleasure. I love what I do. I love my rings. I love my manuscripts. I hope I have communicated that. It's a pleasure to meet you, too. Thank you so much. Thank you.

-Ends-

LINKS

Sandra’s business, Les Enluminures - https://www.lesenluminures.com/

The Museum of the Bible, Washington DC USA - https://www.museumofthebible.org/

The Monuments Men - 2014 film, written by & starring George Clooney, also starring Matt Damon & Bill Murray - https://www.imdb.com/title/tt2177771/