Inside the Jewel Vault with Robin Hansen

Listen Now

|

Robin Hansen. Photo © Trustees of the Natural History Museum. |

Robin's mystic paste Photo © R Hansen |

Skating mouse by Alfred Zimmerman |

'Priceless' paraiba tourmaline. Photo © R Hansen

|

Benitoites, inc trilliant 15.42 ct. Photo © R Hansen |

Morganite 598.70ct. Photo © R Hansen |

Hope Chrysoberyl 45ct approx. Photo © R Hansen |

Robin Hansen Photo © Trustees of the Natural History Museum.

|

|

JCC: I am delighted to welcome Robin Hansen Inside the Jewel Vault. Originally from Perth, Australia, Robin worked in iron ore exploration and then for a partnership of high-end mineral dealers before achieving her dream role to become curator, minerals and gemstones at the Natural History Museum, London, in 2015. Her first book, Gemstones a Concise Reference Guide, has just been published by the Natural History Museum. Welcome, Robin. I can't wait to hear what you've put inside your Jewel Vault for us.

R H: Well, thank you so, much Jessica, for inviting me to come on the show. I'm very excited to be here.

JCC: So, Robin, this book must have taken you years to research and to write. What on earth persuaded you to write a book? A concise history on all of the gems. Surely there can't be a more challenging topic.

R H: Definitely challenging. I can say that now I've completed it. I am very proud of it. So, we had another gemstones book that was published, I think, back in the 80s, through the Museum. And our publishing team had been very keen to have the gemstones book rewritten sort of brought up to date. And it was something I was quite interested to do because I thought - Well, it would be really great to pull together sort of everything that I kind of already know about gemstones that I learned during my gem diploma. And things that I'm learning on the job now that I'm working at the Museum. But also, just the things that I knew I would learn by researching. You know. The different types of gemstones and interesting facts I could find out about them to add into the book. So, it was an absolutely fabulous experience to write. It took far longer than I was expecting. I also, wrote far more than the publishing team had initially asked for. I sort of thought I could just, you know, I'll write a bit every day on the train as I commute to and from work. but no, it took a lot more time and then that's I probably spent about three years putting it all together. And certainly, when people sort of say the last 5% takes you 95% of the time. So, that last bit of just putting a book together does take a lot more time than you realize. But actually, seeing it all put together has just been really amazing and a great accomplishment for me. I'm really proud of it.

JCC: Well, you should be.

R H: It is.

JCC: It's a beautiful book, and it's so, packed with information, all of it current and up to date, really well researched, and you just instinctively, even someone like me, who's a cynical old trade person you can instinctively trust and rely on the accuracy of everything you conveyed in there. The photos are stunning! I mean, just getting all that, you must have had a whole team of people working on your image research.

R H: Yes, I mean, it was really fun, actually, to do that. So, we have a photographer, a photography unit at the Museum. So, I worked with one of the photographers, Lucy, for quite a long time over the years. In fact, when we were in lockdown, I was given permission to go in. So, I would go in one or two days a week, because it was actually the perfect time, because while the museum was shut to the public, I could take lots of the gemstones off display, take them to the photo unit, get them photographed, and then get them back on display again. So, that was one of the benefits.

But it was brilliant. I had a great time looking through the collection and sort of discovering things that I didn't realize that we had, that we could get photographed and working with Lucy to get the best images that we could, and then seeing how they were all, like you said, the book is packed! We put as many images in as we could fit in just to really show everyone what the different minerals look like when they cut into gemstones or what they look like in the rough and what they look like when they're treated, or a synthetic. So, yeah, it was really fun doing the photography bit, it was really fun going through selecting the best specimens to use.

JCC: Well, you have I've just been looking, this is a Dream Gem-fest! So, let's start right in with the first piece. Tell us about this amazing item. Is this the piece that you have a bit of a story about?

R H: I do yes. So, this is a pear-shaped gemstone set into a pendant. And I was thinking when I was coming on the show, I listened to a couple of your other podcasts. I thought, right, I need to pick some gems sort of through the history of my life. And I was trying to think, what was the earliest gemstone I could think of and I remembered this iridescent pendant that my mum had, which I thought was a mystic topaz and remembered playing with it as a child. And it was set in gold, had a gold chain, and, you know, these beautiful rainbow colours and thinking, gosh, I wonder if that was one of the gemstones that really got me interested in gems and colour and sparkly things like this.

So, being originally from Perth, So, my parents are still over there, and I've now lived over in the UK for 20 years. So, sent a message to Mum saying, do you still have this mystic topaz pendant that I remember in my childhood? And Mum wrote back going, I never had one. I just looked up mystic topaz, and it looks lovely, but now I never had a pendant. I'm thinking, oh, my goodness, is my whole memory as a child is based on this gemstone that doesn't exist, bless her. I said, could you go and look. Because I still have some of my things stored at their house. Could you go and look through my things and just see if you can see this pendant in my jewellery box there?

So, anyway. The next day I got back this photograph. That image that we can see here. Showing this pendant which is clearly not topaz because it's got this big conchoidal fracture through it rather than a cleavage. Because I'd remember it being cleaved and sort of thinking, oh well. You know. You are thinking, well she did give it to myself and my sister. The children to play with! And maybe letting children play with a topaz gemstone wasn't the smartest, if it's got sort of damaged or cleaved. But actually, this lovely conchoidal fracture means it can't be topaz. So, it is paste. And its - the facets on the back have been painted different colours to give it this beautiful sort of iridescent appearance. So, anyway, Mum did locate it, So, thankfully, I hadn't completely imagined it, but perhaps she doesn't recall having it as a gemstone herself, but she thinks maybe because at the time she was teaching gemmology that perhaps someone had given it to her as an interesting gemstone and said she'd shown it to us then. And that's why I remember it – so it is still a gemstone from my childhood. It just hasn't - my memory is not quite the same as I think, what the actual story is.

JCC: Well, this is even better because we just discovered not only have you set your mind at rest about the existence of this fantastical object, but now you found out a little bit more about your early career and your early interest. But we've just discovered your mum is a geologist. So, tell us about this – there are not too many guests whose mums are geologists!

RH: She studied geology at university and then also, gemmology. So, she didn't become a geologist after. She then did a diploma of education, became a science teacher, and then later worked at a university, but I think because she always had that big interest in geology, and then she was involved with the Geological Association over there and doing teaching and stuff. So, I think that's where a lot of my interest really comes from in my childhood. We go out for picnics up into the hills outside of Perth, and we'd always be looking at the textures in the rocks and that sort of thing. So, yeah, So, I definitely got my love of rocks and gems from my mum, which is great. And then when I went to university, I didn't know what I wanted to do, except it was, something in science. My dad is also, a science teacher, So, definitely science in the blood. And Mum was like, oh, just try one unit of geology. You might really like it. And I loved it. And so, that was it. That became the focus of my degree and, sort of went on from there.

JCC: But this was the very piece that inspired you, in an interest in sparkly beautiful gems as opposed to rocks and minerals. But you, then mentioned that you went on and worked in iron ore exploration. And then in my intro, I mentioned, of course, that you also, worked for a mineral dealers. So, tell us about that. Yes, that must have been an amazing job.

R H: It was a fantastic job. So, I worked for a partnership of high-end mineral dealers, one here in the UK. And one based in California in the US. and it was a great job. I sort of thought I knew a lot about minerals before I started working at the job. And then when I began, I realized that actually, I didn't know much at all. There was this whole world of mineral collecting, but also, just to learn about all the different minerals but what they look like, what particular locations they come from around the world. and I got to see some absolutely incredible specimens and we exhibited several mineral shows around the world, So, I got to do a bit of trouble as well. So, there's uh, the Mineralientage, which is the one in Munich in Germany; there's one at Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines in France. The Tucson Gem and Mineral Show, which is obviously the biggest one in the world, which happens every year in Arizona. And also, the Denver show. And I also, once got to go to a mineral show in Tokyo, which was really exciting. So, yeah, really fabulous job and spent most of my time here in the UK. And probably about three months of the year I was over in California as well with the business partners.

JCC: Wow. And big-name mineral collectors?

R H: Lots of big-name mineral collectors. It's quite interesting actually, the sort of people that you learn are interested in minerals. So, yeah, but it's quite an interesting business, I think. It is a fairly small community, lots of fun and because people are collecting for their passion and every mineral specimen is unique. So, for them, it's that treasure hunt of trying to find that individual mineral specimen that fits perfectly within their collection, which was really lovely, to help, you know, people find that specimen. And also, because people collect minerals for so, many different reasons, whether it's because they think they just look beautiful or if they're a systematic collector and they want to get one of every rare mineral, or they're particularly interested in sort of the Cornish mines. So, they just want to collect Cornish minerals or So, many different reasons that people collect them. It was a really fun, really fun job.

JCC: It must have been because you were there for some time, weren't you?

R H: Yes, about uh, seven or eight years, I think I was working there.

JCC: You mentioned also, that was based here in the UK with some travel elsewhere and some other time spent in California. So, at what point did you make the big step to come across all the way the other side of the world, the correct side up in Britain and live here?

R H: Uh, So, I had already moved to the UK before I went for the mineral dealers. So, I think following, when I worked in iron ore exploration for around three years and then Perth is quite a quiet city, I have to say. So - you’re in your early twenties, and we had some friends who'd moved to London and were having a great time and so, much to do and see. And also, the fact you could travel from London and be in Paris in a different country in 40 minutes was amazing because Perth is just such a remote city. So, we thought perhaps we'll come over for a year for London, get a working holiday visa. Yeah, we moved over here, and my husband, my now husband who I came over with, he got a job working for a company, and I got a job working there as an admin assistant. And then, the funny connection the mineral dealer. So, one of my friends from university married an Englishman who was also, a geologist, and then moved over to Perth. And the mineral dealer was one of his best friends. So, I sort of got introduced to him, like, at that time, the mineral dealer was looking for someone to come and work for him. So, I thought I'd be nice to look at rocks again. And so, that's how I sort of got that job. And then, that's how I was already living over here, and then would be based still in the UK. And then a bit of time over in the US.

JCC: Well, you did say it's a small world. So, there you are!

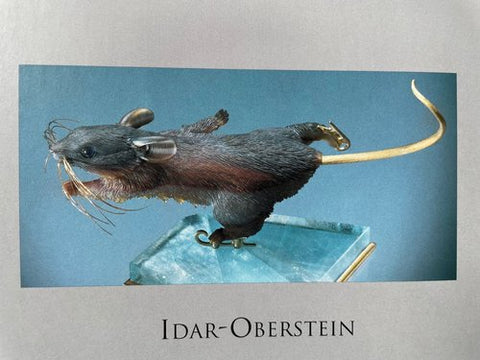

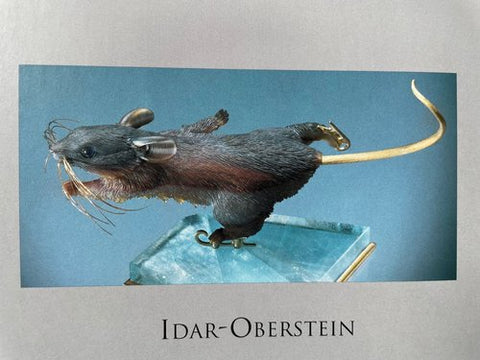

Bowers Museum catalogue image of carved agate and gold mouse, carved by Alfred Zimmerman

JCC: Are any of the pieces in your vault from this time working for the mineral dealers?

R H: Yes. So, the second piece I put into the vault is a carving of a mouse, which is ice skating. So, when I was over in California, I did get lots of opportunities to go and visit some of the different museums. So, down to San Diego County Museum, also, to the GIA, to their Carlsbad campus, and look at some things there. And also, the Bowers Museum. So, my boss over in America, they're quite closely associated with the Bowers Museum. And they took me to see this exhibit, which was the Exhibit of Light and Stone. And this was the collection of Michael Scott. So, Michael Scott was the first president of Apple Computer.

JCC: And also, one of the most famous of the big mineral collectors.

R H: Yes. Yeah. So, it does just have an absolutely phenomenal collection. So, part of the collection was on display here and this particular one I remember seeing, and in fact, my mum was over at the time as well, and also, came to the exhibit with us. And both of us just remember this gorgeous carved mouse. Carved out of agate, and it's got some gold whiskers and ice-skating shoes in gold. And it’s skating on this piece of rock crystal, which is to represent the ice. And I just remember seeing it, we were like, oh, this is just so, gorgeous. And I've just always been really amazed at people who are able to carve these three-dimensional objects out of different rocks and minerals but make them look like they're alive. And also, especially with these more opaque materials, not knowing actually, what do the colours do in the middle, and yet being able to work that into the carving and utilize that to make these incredible sort of sculptures.

R H: Yes, So, this particular one, unfortunately, I haven't got the credit for who carved it, but I think it's a gentleman, Alfred Zimmerman, who worked under Gerd Dreher, who's known for very similar sort of animal carvings, and both based in Idar-Oberstein. And I've since had the pleasure of meeting Gerd Dreher’s son, Patrick, and hearing him talk at several conferences and, you know, seeing lots of images of the carvings that they've also, done. And, yeah, they're just so, sweet. So, many of them with a little mice or frogs and that sort of thing.

JCC: They are little works of art ah, aren't they? And this is just charming, the way that the movement has been captured. I love the way that his whiskers are sort of swept backwards away from his face as he pushes through along the ice. So, there's a little tail and a whiplash that's behind him. It's just adorable.

R H: You could just really imagine the movement and the wind blowing. Ruffling its fur.

JCC: A little speedy mouse. Gorgeous. Well, no one at this one stuck in your mind because it's totally, delicious. So, we have two pieces now that tell quite a lovely story of, your early, inspiration and fascination with gems and minerals. So, that's two pieces. What's the next item in your vault? It’s a little bit different?

|

R H: The next one I've chosen is a paraiba tourmaline gemstone. So, I love tourmaline. I would say they're probably my favourite gemstone, I think, because they come in, you know, So, many different colours, but also, the fact that you can get the gemstones with more than one colour in them but I also, love blues and turquoises. That would be sort of my favourite colours. So, the fact that you get these tourmalines that are, this amazing sort of neon blue colour is, like, the perfect combination for me and the gemstone that I have here in the photograph. That's my hand that it's resting on. So, it's, a particularly large gemstone. So, I was shown this at the 2016 Munich show. I was walking around with one of our colleagues and talking to some dealers and sort of got a shown this. I was like, ‘Can I take a photo?’ And I was just in heaven, just seeing a gemstone of this size and quality and just magnificent colour. So, I thought, yeah, this has got to be one of the favourite gemstones that I've seen. I thought, I definitely need to include a paraiba tourmaline into my vault. JCC: Yeah, I can quite understand. This is exceptional, isn't it? Do you remember the size of it and how much it was worth? R H: I don't remember the size, and I had a look to see if I had a notebook where I might have written it down, but I couldn't find anything, unfortunately. And the price was definitely one of those you don't ask the price. JCC: But no, if you had asked the price, they probably wouldn't have allowed you out of the stand because they would have gone “Ah we got a sale!”. But it is beautiful. That photograph just, shows the blue, sky blue, the most intense sort of aqua-blue that you've ever seen. It's just glorious. And so well, cut as well. Well, if you had it, what would you make out of it? Because I know it's sitting on your fingers here, and it's covering up almost an entire length of knuckle. Half your hand has disappeared! |

Beautiful paraiba tourmaline which Robin saw at the Munich show in 2016. |

R H: I think it would have to be a pendant. Yes. I think it would be too big for a ring. And also, I'd be worried that I'd knock it on something. If I had it as a pendant I'd feel it was much more protected, but yeah, just imagine having it as a drop, maybe with a few little accent stones or something, but nothing that would take away that would be definitely the star of the show.

JCC: Yeah, I can see why that's definitely in your Vault. Well, that's three just stunning gems and jewels. So, tell us, what is item four? It's not actually one item, is it?

A whole case of the best benitoites in the world, Munich show 2017.

The world’s largest faceted benitoite is the trilliant at the back15.42 carats; the kite is the second largest 10.47ct. Photo © R Hansen

R H: No. So, it's more, I guess, the grouping. So, it's a benitoite gemstones. So, benitoite, again, it's another one of my favourite gems. it's quite a rare gemstone. A lot of people haven't heard of it. It's a barium titanium silicate mineral, and it's only really found in gem quality in one location. And that is from the San Benito County in Southern California, which is where it's named after. So, again, this was a gemstone that I was introduced to while I was working for the mineral dealers, obviously the American dealers based in California. And again, I think my interest in it was because it was blue, but also, because benitoite has very high dispersion. So, you can see the beautiful rainbows, the fire in these gemstones in the picture, so, its dispersion is close to that of diamond. Although sometimes when you get the darker blue colours that can mask the dispersion. I think that's where my interest came. I thought, oh, it's like having a blue sapphire, but with the fire of diamond.

JCC: Yeah.

RH: Fabulous. I actually have my wedding ring is set with beneath white gemstones. Yeah, something a bit different. So, I bought the gemstones and had it made up. So, yeah, I'm not sure if you can see it through the camera, then.

JCC: I wish you could. No, I can't really see it through the you might have to send a sneaky bonus picture of that because I don't think I've ever seen a wedding ring with benitoite set into it, let alone a little collection of them. So, good for you. So, that's the mark of a true connoisseur.

R H: So, the collection of gemstones here. So, again, this was at the Munich show. This was in 2017. And every year, they have special exhibits with, lots of different gems and minerals from around the world, depending on what the theme is for the year. And this particular year, they had a whole case of benitoite and the best benitoites in the world. So, you can see here this collection of cut gemstones. So, the trilliant, the one at the back, is, in fact, the world's largest faceted, benitoite gemstone. So, it's 15.42 carats. So, not particularly big gemstone and benitoites, the majority of them are less than one carat. And this is partly due to the crystals, the sort of a triangular like a sort of flattened triangular shape. And it's also, strongly pleochroic. So, the way they need to orientate the gemstone within the rough in order to get the best blue colour means that you end up with very small gemstones. So, to have one that's over 15 carats is quite incredible. And the kite shaped one, which is just to the left of that in the image, is the second largest. And I think that is 10.47 carats. And then I also, sent through a photo of the whole display case. And in that you can see this magnificent, benitoite and diamond necklace. And in fact, I was just flipping through an article in ‘Gems & Gemmology’ (magazine) from 1997, which talks about benitoite. And it has pictures in it, these two gemstones, and also, the necklace. And it credits them at the time to Michael Scott. So, again, I'm not sure if they're still in his collection. But yeah, these more magnificent jewels, that part of his gem and mineral collection.

JCC: Yeah, he must have so, many of the best, the tops, the biggest, or whatever it would be anyone's guess what's in there? Maybe one day I'll get to ask him to pick six…

R H: Yes, that would be fabulous!

JCC: …on this podcast that he would be willing to share because he must have some real treasures. Wow. Well, look, thank you so, much. We haven't had any benitoites on the podcast yet, so, it's lovely that you shared your enthusiasm, with this beautiful gem and explained, a little bit more about it. And it is the most beautiful. I love the parti-coloured ones that you've chosen as well. And it's really nice to see, in the display case some rough, which displays that habit that you've mentioned. So, it's very special.

R H: Yeah. Beautiful gemstone - really is.

JCC: That's four fabulous picks for your fantasy vault. We've got the mystic quartz. Well, mystic paste pendant!

R H: Mystic paste.

JCC: We've got the carved mouse, who's skating serenely and at speed across the rock crystal ice. We've got this fabulous paraiba tourmaline, which is the bluet, bluest, blue, and biggest, biggest drop. So, that was a fabulous pick. And now we've got an entire caseload of benitoite gems. So, what is item five? I think you’re going for something bigger and even more beautiful!

R H: So, for the last two, I've chosen both from the collection at the Natural History Museum, which I'm really honoured to be able to look after. So, for jewel number five, I've chosen a morganite gemstone. So, it's 598.7 carats, so, it measures five one centimetres across. And we believe it's the largest, flawless faceted morganite in the world. And it is absolutely stunning. It's a proper bubble-gum pink colour. And, yeah, just so sparkly and fabulous. We have it on display in our Vault Gallery. if you get the chance to come and have a look at it, the photo I've sent now is from it on display.

Crystallised Joy. Magnificent morganite cushion shape 598.7 carats, 5cm centimetres across. The largest, flawless faceted morganite in the world, in the collection of the Natural History Museum, London. Photo © R Hansen

JCC: Mhm, and so, that's in the vault part of the, which is at the back of the mineral gallery, isn't it?

R H: Yes, that's correct.

JCC: Yes. And that is as close as most people will ever get it to walking Inside a Jewel Vault.

R H: Yes. it's lovely. So, morganite of course, is the pink variety of beryl, and it was first discovered in Madagascar, and this gemstone comes from Madagascar, and we acquired it in 1913. So, only three years after morganite was officially discovered and named, which is quite exciting. So, one of the great things about working with the collection is it's so, historical, but you can look back and find, you know, these really interesting stories behind the gemstones, or also, looking at the dates of acquisitions when they came into the collection. You can kind of see this history of when different gems were found and when they were found in different locations around the world. This is not only an amazing gemstone, but a very early on one that was found as well.

JCC: And you being the curator of this fabulous collection, you have access to all the archives and all the stories, so, you can share and wonder at that, as well. So, why have you chosen this morganite, apart from the fact that it's very beautiful? Because, you know, this is a piece that you must walk past most days. So, why have you chosen to put it into your own fantasy Jewel Vault - if it suddenly isn't on display will we know where to go!?

R H: Well, it has, in fact, just been off display for a couple of years. It was part of the museum's Touring Treasures exhibit which left, I think, in 2018- 2019, and has been around the world on display there. So, we've only just received it back, and it's only just gone back on display in the last month or so. But when it came back and we sort of received the box back and we opened the lid, and it was sort of white plastazote inside, and there was just almost like this beam of pink loveliness that kind of came shooting out of the box. It was just so glorious. And then to put it back on display in the vault, where we've had a gap for it for the last couple of years, and it's sitting next to a large morganite crystal. Yes. It's just magnificent. And every time I walk past it, it just made me feel so, happy to look at it. I thought, I definitely have to include this.

JCC: So, it is crystallized joy. I love that. That's wonderful. What a description. Thank you for choosing that. And so, again, I'm going to ask you the same story, because you obviously have a penchant for setting gems that you like. So, how would you set this particular beauty? It's enormous.

R H: It is enormous. In fact, I think it probably is almost too big to set.

JCC: No!

RH: Definitely too big for a ring. I think it would have to be some sort of large necklace. I don't know. Just the weight of it. I think it's just so big. We'd have to consider it carefully.

JCC: It would look great with a paraiba tourmaline, too!

R H: Yes, it would –

JCC: Imagine those colours

RH: right next to each other!

JCC: Showstopping!

The historical Hope Chrysoberyl, a ‘Superb chrysolite… a matchless specimen’ approx. 45ct, in the Collection of the Natural History Museum. Photo © R Hansen

JCC: Wow. Okay. Well, that's a great choice. So, I completely see why you've chosen this for your fantasy vault. And the final piece, we've got, this one space left. So, tell us, what is number six?

R H: So, number six is a chrysoberyl. It's the Hope Chrysoberyl. It's almost 45 carats. We also, have it on display in the Vault Gallery. And it's a circular, brilliant cut. And again, it's just a really beautiful stone. So, historically, this was one of the finest chrysoberyls known. And it belongs in the collection of Henry Philip Hope, who most people would know of as being the former owner of the Hope Diamond, which, of course, is the blue diamond now in the Smithsonian Collection. And we have it on display. And I think it's just got this really wonderful lemony-lime colour. But I think a lot of people actually overlook it because as you walk past the case that's in you've got sort of imperial topaz and tourmaline and opals and all these other magnificent gems as well with it. But when you really look at it, it's just such a bright, lively stone and this wonderful colour. And also, again, going back into the archives. So, Hope’s collection was catalogued by a gentlemen Bram Hertz and it was published in 1839, which is actually the same year as Hope's death. And it was figured and catalogued and numbered as “chrysolite number one”. And it has this absolutely beautiful description, in fact, if we've got time, I'll read you the description from the catalogue.

“A most superb chrysolite, nearly of circular form and of a deep yellowish green tint approaching the colour of periodot and most admirably cut like a brilliant. This extraordinarily fine gem is of the greatest transparency and brilliancy and free from any speckled flaws. Its uncommonly large size and great perfection entitle it to be called a matchless specimen.”

JCC: Well, I think that's an apt description, isn't it?

R H: I think it's just beautiful. I'm also, quite pleased, as a curator, I don't need to write descriptions like this for every gemstone because it's just so wonderfully written. I don't think I'd be able to live up to that. Again, it just has that wonderful history to it. So, after Hope died in 1839, the specimen was passed through the family and then it was auctioned by Christie's in 1866 and it was purchased by the mineral dealer James Reynold Gregory. And possibly he was purchasing on behalf of the museum because it then came directly into the collection from him. But the other really cool thing is that one of my predecessors had done some research looking in the archives and we have a letter that’s dated in 1821 from a gentleman Henry Hewland, who was a mineral dealer, to Edward Thornton, who was the minister for Portugal. Now, Hope had purchased lots of gem minerals from Hewland, including a very fine Brazilian chrysoberyl rough for which he paid £250. Now, according to this letter, it produced a 44 carat gemstone. And so, we think this has to be this gemstone because this one is just under 45 carats. So, by looking at that as well, we can sort of infer that it probably means that this gemstone came from Brazil and that would have been cut either in 1821 or before that date. So, it's just really lovely that we can kind of work out all this extra history about these gemstones. It's not just a chrysoberyl we have on display. It's just got all this whole story behind it, which is really, really lovely.

JCC: Yes. And can you imagine, the extraordinary reception of a gem this size from a new source? Because the discovery of the gem fields in Brazil really completely revolutionized jewellery history, didn't it, in the preceding 50 years? So, to have a gem of this size and then to have it cut in such a, you know well, it's nearly circular. Well, it looks circular from here. But to have it cut, almost like a brilliant, they must have been, considerable - they must have required a considerable amount of skill. So, it should have probably went to a very good stonecutter. Well, it's wonderful that you have all of this provenance, because this is what must be one of the great joys of your job, your current role?

R H: It is. I do love it. I'm really interested in the historical side of the collection. And when you find, you know, these sort of titbits of interest. And every specimen we have, I mean, the mineral collection itself is about 180,000 specimens. So, within really yes. And we're actually one of the smallest collections in the museum. There's, over 80 million objects in the museum itself.

JCC: I would hate to do your stocktakes!

R H: Well, I did work out when I started. If I stay in this role until I retire, I don't think I can physically look at every single specimen we have in the collection. Like, there just isn't enough time.

JCC: Oh, isn't that tragic? Can you imagine? Well, I have to get you on in a few years, then. And you'll have a totally new Vault.

R H: Yeah, all the new things I might have uncovered.

JCC: So, what is it you're currently working on? Because, the last two years have obviously been a major issue for sharing the collection. But, have you had some projects that you've been working on meantime?

R H: Yes, so, I mean, we do do a range of things we're looking ahead in the sort of the next two years, we're going to be doing some gallery enhancement projects. So, looking at sort of just improving some of the galleries the look and feel, updating labels, that sort of thing. So, that's always really exciting program to work on. And then other things that I do in my role, so, registration of new specimens. So, we haven't had too many new specimens in the last couple of years because we haven't had the opportunity to go out looking for them, but certainly that's another part of my role. And then I'm also, doing quite a bit of work with the Gem Collection, again, sort of trying, to enhance all the information that we've already got on it. So, the gem collection itself is about a four and a half thousand specimens and we sort of say, if it's been cut and faceted and it's used for adornment, then that's what defines it as being part of the Gem Collection. But we also, have a lot of worked objects as well. So, different carved bowls and vases and that sort of thing. So, yeah, so, it's making sure they're all appropriately housed so that they're protected and preserved for the future and that they're available for research and that we're adding new information about the specimens as we sort of learn anything new about them or, you know, uncovering this kind of historical information as well. Just adds so, much more to each specimen.

JCC: Yeah. The wealth of detail. And so, have you got any items on a shopping list for the Natural History Museum Gem Collection?

R H: Well, the big one

JCC: Or that would be telling…?

JCC: Giving the game away?

R H: Well, a big paraiba tourmaline is definitely the top of my wish list because we don't have a Paraiba gemstone in the collection. So, that certainly, something that we'd love to get. A lot of the new acquisitions that we've been doing have been sort of interesting, rare or unusual gemstones. So, in fact, in the last couple of years, we purchased a faceted gemstone which is made of halite, So, that's rock salt. So, your normal table salt. So, incredibly difficult material to work with because it dissolves in water. So, they had to come up with a special method of faceting it, using I think it was using acetone or something like that on the cutting wheel. So, we've bought some really interesting and unusual sort of gemstones. Quite rare materials that you wouldn't normally think of for gemstones as well. Uh, but, yeah, definitely Paraiba. That's top of my list for the collection

JCC: But I hope you've got deep pockets for a paraiba tourmaline that would be worth displaying, because they're very expensive now, I've got a number of clients who should have bought them when they first came out. And the lack of material now for these really intense colours is, dwindled. They tend to be treated, don't they? So…

R H: Yes. And I think it is amongst the highest per carat value of many gemstones, I think the Pairaiba, normally, especially if they're untreated.

JCC: Yeah. Well, all of the gems that you've chosen are pretty, ah, pricey, aren't they? A good specimen.

R H: Yes.

JCC: Or a “matchless specimen” would be very pricey!

JCC: So, we've come to the bit where I have to ask you the worst question of all, because out of these six amazing objects, you have to just choose one if all else was going to be lost. So, if we run through what you've put in already, you've got your mystic pendant - the gem that sparked your lifelong career and love of gems and minerals. We've got the carved agate mouse, we've got the paraiba tourmaline, this benitoite display of gems, the morganite gem, which is just put back safely in the vault recess of your own museum, and the Hope Chrysoberyl, which is one of its mates. What would you choose if you could have any one of them?

R H: It is such a hard decision. But, I think I would have to go for the morganite gemstone. It's just so, incredible, especially when you see it in person. Yeah. It's just stunning.

JCC: And it would light you up with its rays of joy every time you looked at it.

R H: I think so, it would. It really would.

JCC: I love that. I love the fact that you've chosen that. So, thank you for sharing. It's just been a joy speaking to you!

R H: Thank you. Now, it's been a real pleasure. I mean, I do love talking about gemstones, I have to say. So, yeah. It's been a real pleasure to be able to share them as well.

JCC: Well, it's been real honour. So, thank you so, much for sharing the time and this amazing Vault with us.

R H: Thank you.

-Ends-

Links

Natural History Museum (NHM) London - https://www.nhm.ac.uk/

Robin Hansen’s NHM staff page - https://www.nhm.ac.uk/our-science/departments-and-staff/staff-directory/robin-hansen.html

Natural History Museum mineral collection - https://www.nhm.ac.uk/our-science/collections/mineralogy-collections/mineral-collection.html

Mineralientage - https://munichshow.de/en/home-en/

Sainte Marie Mineral fair - https://www.sainte-marie-mineral.com/

Tucson Gem & Mineral Show - https://www.tgms.org/show

Denver Mineral show - https://denver.show/

Tokyo Mineral Show - http://www.tokyomineralshow.com/

Dreher Carvings - https://www.dreher-carvings.com/en/history